Introduction

Volatility is likely to be the new normal

The past year has been noted on the political scene for its upsets and consequent volatility.

Markets were taken by surprise by Brexit. Similarly, earlier this month, Donald Trump surprised the pollsters yet again by winning the US election, even though, the pollsters may argue, he did not get the popular vote.

Over the past 11 months, investors began to realise that volatility is becoming all too real and normal as a prospect sterling crashed through floor shortly after the EU Referendum, and gilt yields plunged as more investors looked for safe havens.

With the unexpected becoming the new normal, some investors are in a state of panic. What will happen next year in the French elections? Marine LePen is hoping her chances have strengthened on the back of the wave of resurgent populism.

The problem is that as the politics became more unpredictable,investors worry that this makes economies, and future prosperity, unpredictable. But this equation is by no means certain.

As experts point out, if you had invested a small amount of money throughout the past 50 years, you would still be sitting on a sizeable investment, despite several stock market crashes, recessions and sovereign debt defaults.

The usual rules of investing for the long term and building a balanced portfolio have come into play. It is during times of uncertainty that it pays to have an investment manager or financial adviser with a few grey hairs who has seen uncertain times at least once before.

There are also opportunities; some are even saying that we will see a revival in the American economy on the back of the Mr Trump’s economic policies of tax cuts and infrastructure investment. Whether this is sustainable over the long term is open to question.

But now might be the time to consider other options, such as infrastructure as a form of investment, which has struggled to gain mainstream acceptance, or other alternatives, such as private equity.

It may make for politically interesting times, but for investment professionals, the political changes are a time for holding one’s nerve and waiting for new opportunities to emerge.

Melanie Tringham is features editor of Financial Adviser

Keeping a cool head in volatile markets

When investment professionals look back in 10 years’ time, will they come to see 2016 as the year when volatility increased and electorates became more and more unpredictable?

Perhaps, but despite some obvious nerves among the investment community, attempts are being made to calm the waters.

Justin Urquhart Stewart, co- founder of investment manager 7IM, says: “Investment professionals are nervous. What the investment industry likes is for things to run in a nice, stable way. If you give them a shock,everything they tell their clients no longer applies.

“But in the longer term it will be fine. That’s not to say investments will always be good, but the longer-term picture is how you create confidence with people.

“The industry can look like a rabbit in headlights, but they tend to be the younger ones. They either don’t know what to do or think they can be terribly clever and be a hedge fund manager, and buy things that are dangerous.”

The past year has been eventful. It started off with intense volatility and stock market losses due to perceived slowdown in the Chinese economy and a tumbling oil price, and then the unexpected Brexit vote happened in June, followed by the shock of Donald Trump being elected US president earlier this month.

Mr Urquhart Stewart said: “I was at a conference recently, and professionals in the audience – even accountants – were asking: “Should I be selling everything and going into cash?”

“That’s a really stupid idea. As soon as you do that, you will start to lose money.

“People are very, very frightened. They were shaken by Brexit, and they were really shaken by what’s happening in America, and this gives people the perfect excuse to do nothing.”

“The electorate has become really unpredictable, but it’s very difficult to put together a portfolio that will genuinely be immune”

But as with Brexit, many of the investment arena’s old hands are calling on their experience and convincing investors that it really is not that bad, and in the words of Mr Urquhart Stewart to “fall back on some old-fashioned investment rules”.

First of all, he highlighted the “power of compounding”. This means that if one reinvests the dividends of one’s shares, the returns are exponentially much higher. Mr Urquhart Stewart says: “Say, for example, 69 years ago, granny left you £100 and you put it into the market.

“Some 69 years later, you would have £9,000. The thing to remember is time in the market rather than timing the market. Over 20 years, if you took £20,000, you would have gone to £33,000. But if you missed the best 40 days – which often happen after the worst 40 days – you would have lost money, and you would not know when the best 40 days are.”

As an investment manager, Andrew Herberts of Thomas Miller Investments is surprisingly sanguine. He says that he might make a few adjustments to his clients’ portfolios, but is not gearing up for a massive shock.

He says: “It’s so difficult to predict the uncertainty. The electorate has become really unpredictable, but it’s very difficult to put together a portfolio that will genuinely be immune.”

He urges adjusting portfolios slightly, so that “if we do get a pullback, there will be some properties of the portfolio that will be resilient and hold up well”.

He sees opportunities with the Trump presidency, at least on the investment side. He says: “The key thing is we still do not know much about the Trump presidency. He gave us an awful lot of policy ideas in his speeches running up to the election, but there was limited detail, so it was difficult to say X or Y is a policy.”

His proposals on tax cuts, for which he is likely to get backing from the Republican-dominated Congress, would be good for consumers and will build inflation in the system, which will in turn prompt interest rates to rise.

Mr Herberts says: “One of the issues the banks have had in a really low interest rate environment is [that] it is difficult to make a margin on your loans. [Trump’s changes] might start that moving back in the right direction.”

But over the longer term, this may not be so good for the American balance sheet. The US Federal Reserve has to get its timing right on when to make any interest rate move so that it is not behind the curve.

The main change is less reliance on what had been regarded as completely safe bets, such as government debt. As more uncertainty moves into the political space, so its investment expression has become more volatile.

Melanie Tringham is features editor of Financial Adviser

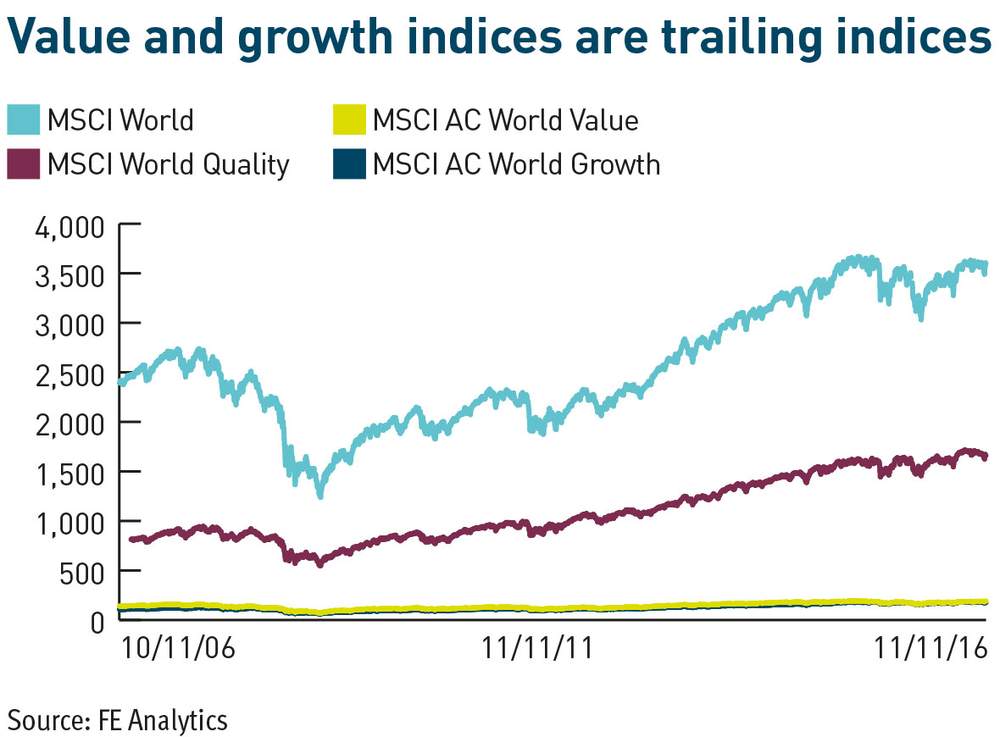

Regardless of one’s perspective, today’s markets are packed with unique dynamics. Since the financial crisis in 2008, the world has been driven by an unprecedented mix of monetary easing and asset purchases that has instigated, in broad terms, a mis-pricing of risk.

With no distinct cost of capital and limited creative destruction, markets have been on edge, focusing on themes such as quality, safety or yield at almost any cost. Visibility of earnings in particular has been trading at a large and increasing premium compared with other parts of the markets.

Many of these themes tend to pay dividends and so investors have flocked to such names. However, the operative words are “tend to”. Not all dividends are made equal. Therein lies opportunity and danger.

Despite being regarded as a single homogeneous category, dividend-paying stocks vary just as broadly as the rest of the market and require the same level of scrutiny as other investments.

For instance, not all allegedly safe stocks provide dividends and conversely, dividends do not directly correspond with safety, however one defines it.

Applying a bottom-up approach will help protect investors from dividend cuts

Relying on a dividend stock’s supposedly safe connotations is no substitute for understanding the business underlying it. Investors should first decide on why they are searching for dividends in the first place.

Investors who need yield to meet set liabilities or living costs are most at risk because they are, by definition, price insensitive.

Having presumably been pushed out of government debt into credit and equities, these investors have no choice but to buy high dividend stocks regardless of the underlying risk.

Although a high dividend yield often betrays poor fundamentals. In the first quarter of 2016, many UK stocks cut or reduced their dividends to the extent that £19bn of assets fell out of the income fund category.

Due to the large-scale cutting of dividends, funds were no longer able to produce 110 percent of the index’s yield as required by the Investment Association’s definition of an income fund.

The US in particular is a fertile ground for stock buybacks because many corporates there have large cash reserves

Dividend coverage and payout ratios, as well as management’s track record of capital allocation, can give investors insights into the likelihood of realising the dividend advertised by the company.

A dividend cut is often the right thing for a company in trouble because it releases cash flow to deploy in restructuring, but this is little comfort for an investor requiring yield today.

For investors who enjoy the luxury of a long-term investment horizon in these uncertain times and are more focused on total return, the choice is more varied.

This framework tends to promote more rational decisions when looking at dividends.

One approach is to focus on rising yield rather than starting yield. Names with low starting but steadily growing dividends can produce material outperformances on a total return basis when compared with either non-dividend stocks or those with high and unstable dividends.

Re-investing the growing yield will further compound investor returns and produce huge rewards for investors willing to understand the value of stable dividends.

Taking the S&P 500 as an imperfect example: the price return of the index since January 1, 2000 is more than 43 per cent, but the total return achieved by reinvesting dividends is just short of 100 percent.

Throughout the period, the dividend yield doubled from 1.1 percent to 2.2 per cent. Despite some of the discussed pitfalls, the huge potential benefit of dividends to returns is clear to see.

Looking at overall yield rather than just dividends can also help investors tailor investment decisions to their needs.

The US in particular is a fertile ground for stock buybacks because many corporates there have large cash reserves and few opportunities to spend it on high return projects.

Different areas tend to use the most efficient method of returning cash to investors depending on the tax system in place.

By introducing buybacks into their frameworks, investors give themselves another tool to exploit and more flexibility to avoid the most precarious dividends.

Understanding the underlying stock remains the most important factor in dividend investing. Applying a bottom-up approach will help protect investors from dividend cuts.

It is unclear what will trigger the unravelling of the crowded trades of recent markets, but the broad uptick in yields across the globe may herald a mass re-pricing of bond proxies if it continues. Prudent investors would do well to limit their exposure to such weakness.

Christopher Meurice is associate director at Signia

Why chasing high yields can lead to danger

This year has been a real roller coaster ride for investors and savers alike, and the Brexit vote was a real shock both politically and financially.

For investors and savers, it raised so many questions about the potential economic outlook for UK plc as we set off into totally uncharted waters.

The big question was and still is what effect the result will have on both fiscal and monetary policy. This is further exacerbated by a sudden change of prime minister and a new resident at the Treasury responsible for managing an orderly and considered exit from the EU.

We should be under no illusions that the outcome of the vote on June 23 is anywhere near being clear: the political shenanigans involved will run for some time to come and the outcome is far from clear.

Unfortunately, it is this uncertainty that equity markets are most troubled by, and the manifestation of this uncertainty comes in the form of volatility and whipsaw shape graphs of stock prices.

Brexit threw the UK financial world into turmoil: markets fell quickly as a contagion panic ran like wildfire and the UK pound nose-dived about 10 per cent, and the result was at one time a 31-year low value against the dollar.

Understandably many investors and savers alike have been forced to re-think their strategies when looking for income. Capital growth or capital preservation and stability? Or both?

An obvious consequence of the UK investor heading for more safe homes for their capital has been that gilt yields declined.

What is more, yields on UK credit have slid back. To make matters worse, the global ratings of the UK economy have been downgraded from previous triple-A category.

The reason given by the ratings agencies was twofold. First, that the economic GDP projections for the UK were likely to be less than previously thought. Second, the political upheaval would inevitably create further uncertainty and negativity.

As we move through the final quarter of the year, those comments by the ratings bodies look particularly telling.

Traditionally in times of great political upheaval and market turbulence, investors have attempted to adopt a defensive position by favouring bonds, gold, infrastructure, healthcare and consumer staples.

The problems they face taking this approach are very challenging. First, the interest rate environment has not changed as many people have been consistently calling; the Bank of England has remained steadfast and maintained this record period of below average base rate.

The knock-on effect for savers is of course that their deposit capital is effectively yielding in negative territory when compared with inflation on the cost of living. Although it is still very benign, inflation is still with us.

Since the Brexit vote and the slump in currency value of the pound, it is not going to take long for the increased costs of importing raw materials and food to start to bite and provide some inflationary pressure.

So what does the future look like for investors and savers who are increasingly under pressure to squeeze out yield – particularly so in the case of an ageing population who need to maintain income levels?

There is a real danger for these people and it comes in the form of investment risk. In the heady days of 5 per cent interest rates, it was a no-brainer for many people to avoid the shocks and scared of the equity market and simply stuff their cash into deposit-based vehicle and simply let the interest generated provide some income, albeit with a potential tax liability on some of it.

The brave new world of the post-Brexit vote in 2016 has thrown up a real conundrum for these investors. While all the news was bad and fear was everywhere, the UK market and others elsewhere around the globe have recovered from the initial shock and for the most part bounced back and indeed made some upside gains.

What I suspect will happen is that those people who have adhered to a cautious view on their investments will inevitably have their attention drawn towards equity investing to achieve their goals, while not necessarily fully grasping the risk therein.

The value and levels of the UK equity have been further challenged recently, with the circus masquerading as the US Presidential elections, but interestingly enough have by and large ridden the tide of misinformation and rhetoric and shaken off the Trump Pence factor and continued with business as usual.

How this will impact on the make-up of investors’ portfolios and the balance between bonds and equities is really tough to call, but I suspect that the ongoing depressed levels of interest rates on both sides of the Atlantic will push more people into the active strategy funds and reduce over-reliance on fixed-interest.

Nick McBreen is an independent financial adviser at Worldwide Financial Planning

Advertorial

Investing in uncertain times

Thoughts, ideas and insight for Advisers from the BlackRock UK Income team

While every period has its uncertainties, these feel like particularly febrile times.

A tide is rising against globalisation, manifested in the triumph of populist movements: Donald Trump, Brexit, Italy’s Five Star, plus far right groups across Europe. This is challenging existing political and economic structures.

Some of this political change has its roots in economics. For example, the wealth inequalities created by low interest rates

have undoubtedly played a role. This in itself has created considerable dislocation across equity and bond markets since the financial crisis.

It is a time when these policies are increasingly being reassessed and policymakers are looking at alternatives to stimulate growth.

This is in addition to organic change: Technology continues to revolutionise certain industries and render others obsolete. The same is true for environmental change.

Investors need to try and ensure they are on the right side. In short, it is an environment rife with uncertainty.

Volatility an inevitability

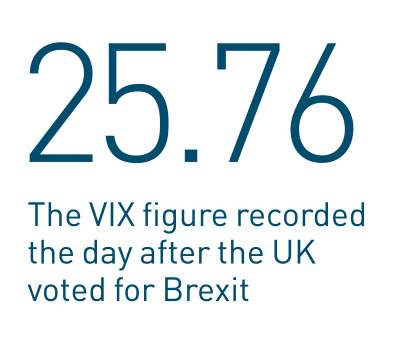

An inevitability in this environment is spikes in volatility: these have accompanied every piece of major political news over the

past year, including China’s devaluation, the Brexit vote and Trump’s election to the White House.

At the same time, investors must steer a course through the anomalies brought about by loose monetary policy – such as negative interest rates – and the impact of a generally fearful environment, where some investors prize safety above all. This has led to an unpredictable pricing environment for both bonds and equities.

Nevertheless, there is opportunity in this mispricing. In an uncertain climate, share prices do not necessarily reflect the

inherent value of the underlying business.

Investors may over-estimate the stability of a company, or they may under-estimate its resilience. Either way, for those that are watching carefully, we believe it should be possible to buy shares in companies we consider attractive for less than our estimation of their real value.

That is not to say it is an easy environment for companies: not only is planning difficult, earnings growth is scarcer in a

lower growth world.

For international companies, political developments – such as Brexit or greater protectionism in the US – may necessitate a change in their business models. Across

the board, it may deter longer-term investment, which in turn impedes long-term growth.

It is an environment where weak companies may be quickly exposed, but it is also an environment in which the strongest companies – those that provide solutions – can fare exceptionally well.

Finding opportunities

Clearly, finding opportunities amid a market where growth is anaemic and share prices are relatively high is not always easy to do. Equally, it is bold to suggest that the market’s estimate of share prices is wrong.

In order to do this, we need to be extremely sure of our thesis. Achieving this conviction requires intensive research and discussion.

We have an experienced bank of analysts

who will interrogate company fundamentals, while our portfolio managers will meet with company management to get

a more detailed perspective on the company’s prospects.

Staying focused

It is a labour-intensive process and, as such, we keep our list of investments concentrated. This enables us to monitor them closely.

It also gives us the capacity to maintain a

‘watch list’ of those companies that we like, but where the share price may currently be too high or there may be another short-term impediment to buying.

Equally, while our aim is to build a thesis for a company and back that thesis with conviction for the long term, uncertain times mean that it is vital to be alert to changes in a company’s prospects.

We focus primarily on analysing companies, but major macroeconomic events such as Brexit can alter the trajectory for certain companies. This is particularly true for politically sensitive sectors such as the banks or healthcare.

This means re-testing our assumptions and, if necessary, being brave enough to let go of a favoured holding when the prospects have changed. With a tight stock list, we have a high benchmark for inclusion and aim to carry no passengers.

Keeping your head

Share price volatility can be distracting and it is easy to be swayed by market ‘noise’.

Investing effectively in uncertain times means keeping your head, not being swayed by every piece of data, or every market event, but analysing them thoughtfully and rationally.

Economic news will influence stock markets, but will influence a company’s real, long-term prospects far less frequently. Recognising what is important for a company’s fortunes is key.

We also believe that it is important to be a student of history, but not a slave to it. History can be a guide, but these times have not been seen before.

Interest rates have never been so low for so long; central bank intervention has never been as all-encompassing. As governments increasingly embrace tax policy as a means to boost their economies, this introduces another element of uncertainty.

Investors cannot predict the future; they can only make their best judgement based on all the available information.

We believe the best defence when trying to manage money in uncertain times is to focus forensically on the companies themselves and to be objective about their prospects in a changing world.

Disclaimer

This material is for distribution to Professional Clients (as defined by the FCA or MiFID Rules) and Qualified Investors only and should not be relied upon by any other persons.

Issued by BlackRock Investment Management (UK) Limited, authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Registered office: 12 Throgmorton Avenue, London, EC2N 2DL. Tel: 020 7743 3000. Registered in England No. 2020394. For your protection telephone calls are usually recorded.

BlackRock is a trading name of BlackRock Investment Management (UK) Limited.

Past performance is not a guide to current or future performance. The value of investments and the income from them can fall as well as rise and is not guaranteed. You may not get back the amount originally invested.

Changes in the rates of exchange between currencies may cause the value of investments to diminish or increase. Fluctuation may be particularly marked in the case of a higher volatility fund and the value of an investment may fall suddenly and substantially.

Levels and basis of taxation may change from time to time. Fund specific risks: All financial investments involve an element of risk. Therefore, the value of your investment and the income from it will vary and your initial investment amount cannot be guaranteed.

Investors in this Fund should understand that capital growth is not a priority and values may fluctuate and the level of income may vary from time to time and is not guaranteed. Where some or all of the fund’s charges are taken from capital rather than income, this will increase yield but decrease the potential for capital growth. Smaller company investments are often associated with greater investment risk than those of larger company shares.

Investment risk is concentrated in

specific sectors, countries, currencies or companies. This means the Fund is more sensitive to any localised economic,

market, political or regulatory events.

Any research in this document has been procured and may have been acted on by BlackRock for its own purpose.

The results of such research are being made available only incidentally. The views expressed do not constitute investment or any other advice and are subject to change. They do not necessarily reflect the views of any company in the BlackRock Group or any part thereof and no assurances are made as to their accuracy.

This document is for information purposes only and does not constitute an offer or invitation to anyone to invest in any BlackRock funds and has not been prepared in connection with any such offer.

© 2016 BlackRock, Inc. All Rights reserved. BLACKROCK, BLACKROCK SOLUTIONS, iSHARES, BUILD ON

BLACKROCK, SO WHAT DO I DO WITH MY MONEY and the stylized i logo are registered and unregistered trademarks

of BlackRock, Inc. or its subsidiaries in the United States and elsewhere. All other trademarks are those of their respective owners. RSM-5586

Managing clients' portfolios amid volatility

The rule of thumb for advisers when it comes to managing clients’ portfolio is to focus on long-term objectives and simply ignore the daily noise of the markets.

However, the markets have made a great deal of commotion in the past year. Seismic geopolitical events, such as the Chinese market correction, the fall in oil prices, the EU referendum Leave vote and, more recently, the shock victory for Donald Trump in the US election race, have wreaked havoc on global markets.

The Chicago Board Options Exchange Volatility Index shows there is a direct correlation between these macro events and peaks in volatility.

There is a sentiment that a highly volatile investment environment could represent fertile hunting ground for the most savvy advisers to make a quick buck.

However, 2015 research conducted by Vanguard, which is renowned for its buy-and-hold portfolios, suggests that performance-chasing is not necessarily the best approach.

The firm found a buy-and-hold approach outperformed a performance-chasing strategy by 2.8 per cent per year on average between 2003 and 2014.

Volatility trading strategies are speculative, or as Mark Dampier, head of research at Hargreaves Lansdown, puts it: “It is like saying if you buy a lottery ticket, you might win the lottery.

“The idea of this strategy might sound quite sexy but in reality, it doesn’t work because it is based on assumptions, or it simply does not generate a lot of money.

“It is difficult to time the market because it is nigh on impossible to predict what will happen in times of uncertainty and volatility. You often find that what’s driving overreaction in global markets is nothing more than speculation.”

Amid high market volatility and, not least, record low investment yield, advisers are faced with the difficult task of managing their clients’ expectations.

Getting clients to ignore the prognosticators in the build up and after a macro event is by no means an easy feat, according to Mr Dampier.

He says: “With the birth of the internet, we have a 24-hour news flow. This makes it difficult for advisers to calm clients.

“Volatility is simply volatility and shouldn’t necessarily affect a long-term investment plan. Unfortunately, people make emotional decisions rather than investment ones.”

The US election result is a good example to show jittery clients that heightened market volatility in response to macro events is likely temporary, according to Jason Hollands, managing director of London-based Bestinvest.

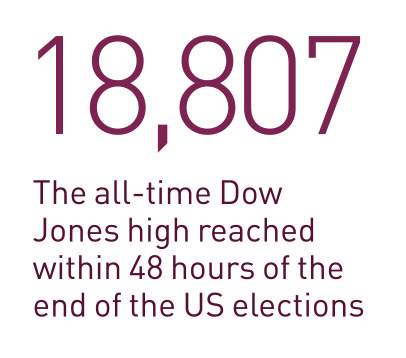

Trump’s win saw a slight dip in the S&P 500 futures, while the Dow Jones at one point plunged by more than 800 points.

However, the indices recovered some of their initial losses and stability had returned by the time they opened the day after polling. In fact, the latter closed at an all-time high of more than 18,807 points within 48 hours of the election.

Mr Hollands adds: “We try to reduce volatility through our asset allocation strategy and diversification – ensuring that we are not overly exposed to the equity market, which is particularly sensitive to volatility.

“The issue is there has been a greater correlation across different asset classes because of the distortion caused by the programme of quantitative easing that has been adopted by a number of central banks. This means that the benefits of diversification are not as strong as they have been in the past.”

The do-nothing prescription in extreme volatile markets might be a bitter pill to swallow for many clients, but it could pay dividends when it comes to accomplishing the goals of their long-term investment plan, Mr Dampier says.

After all, financial plans should factor in volatility from the outset. The portfolios of clients approaching retirement should be positioned in more conservative assets, he added.

The difficultly for advisers is ensuring this approach is not misconstrued by clients as inertia. This idea can be debunked by clear communicating with clients, according to Marlene Outrim, managing director of Cardiff based UNIQ Family Wealth.

She adds that advisers should seek to educate their clients on the likely effect of macro events, such as the Brexit vote, in advance, and explain how their portfolio was constructed to mitigate the effects of either result.

She says: “We are not stock-pickers. We leave that to fund managers. Our job is to ensure that our clients have a portfolio that is tailored to their assets and their risk profile. We do not make knee-jerked reactions.”

She adds: “It is not a do-nothing approach, but more of a sit-tight approach. It is about saying to the client ‘yes, we are going to make some changes to your portfolio, but not because of Brexit or because of a shock election result, but because it is the right thing to do to meet your long-term objectives and risk profile’.”

Myron Jobson is a features writer for Financial Adviser

Looking beyond the traditional paradigm

Traditional assets have come under pressure over the past two months. What has been most stark about this performance is that there has been nowhere to hide, with bonds selling off at the same time as equities. We would argue that this trend is symptomatic of both asset classes being bid up to extreme valuations.

The game is by no means up for investors, but we believe it is imperative they cast the net wider to encompass assets that can offer attractive returns and have helpful catalysts to unlock the return potential implicit in a cheap valuation.

Investing does not come with a crystal ball so making cast-iron predictions is a fool’s folly. However, we believe we can stack the odds of making attractive returns firmly in our clients’ favour by owning a select blend of sectors and asset classes.

Our investment process begins by looking at valuations. We believe that future returns will be driven by the valuation one pays for an asset and the level of economic growth it is exposed to.

The regulated nature of many of these assets makes it easier to pass through inflationary price rises

Traditional assets (that is, sovereign bonds and global developed equities) are expensive and growth rates are low. It follows that future returns are therefore lower and have more risk involved (since investors do not have the safety net of having bought something cheap in the first place).

The chart below indicates that traditional bonds and equities are at their most expensive level for more than 200 years. This contrasts with a low point in valuations, which has been the kindling beneath the fire of asset returns for the past 35 years.

Without getting too bogged down in theory, the bumper returns investors have enjoyed by just owning a simple 60/40 mix (with 60 being the percentage in equities) cannot go on forever. This mix has yielded a return of nearly 8.5 per cent a year for the past 35 years against a backdrop of a 2.6 per cent inflation rate.

Added to expensive valuations is the breakdown in traditional relationships between these assets. Over the past month, we have seen bonds moving in the same direction as equities (correlations are higher than they were in the taper tantrum of 2013). This means there is no natural protection for portfolios and diversification gets replaced by what we call di-worse-ification.

Our approach is to focus on those assets with cheaper valuations (that offer an attractive upside) and assets that have a supportive tailwind in the form of a helpful business cycle. Infrastructure investments are one such example.

While these assets are not extremely cheap, they offer a high and stable yield. They should also benefit from the likely pick-up in spending by governments. Furthermore, the regulated nature of many of these assets makes it easier to pass through inflationary price rises.

Monetary policy has been the go-to tool to stimulate growth and inflation since the depths of the crisis in 2009. While the world would no doubt be in a worse place had there been no monetary response from central bankers, it has doubtlessly become less effective at each turn and raised valuations of traditional assets to ever more eye-wateringly high levels.

It is nigh on impossible to argue government bonds are good value when more than $10 trillion of them (circa 30 per cent of the market) trade with a negative yield.

Monetary policy’s race has very much been run. Governments are waking up to the idea that it is time for them to grab the baton and use low, or (even better) negative yields to borrow money and invest.

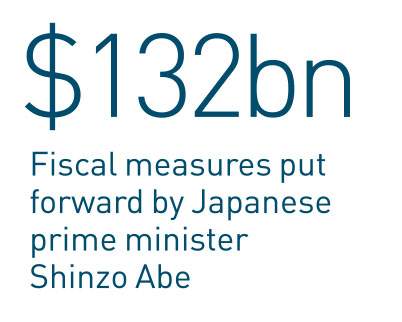

Austerity politics appears to be on the way out. In Japan, we have recently seen the approval of $132bn of fiscal measures put forward by prime minister Shinzo Abe. China is already well under way and the US and the UK appear to be turning a corner.

New chancellor Philip Hammond has said he will move away from George Osborne’s austerity with a stimulus package put forward in the autumn statement this month.

These measures would boost spending expectations, which are already high. Developed market spending is set to double in the next 15 years and developing economy spending is set to almost triple. Much of this spend will likely be on transportation and other things that drive growth: roads, rail, schools and housing to name but a few.

While infrastructure is a theme that can benefit from helpful policy, there are also parts of the market tilted more towards value that can benefit from having a margin of safety implicit in their valuation. Examples would be European and Japanese equities.

Both these markets are trading at significant discounts to the US market (which counts for circa 60 per cent of the global equity market and hence swamps returns if one invests globally), have companies that are growing margins and delivering earnings growth.

These value types of equity markets should also perform better in an environment when interest rates are rising. Although this may well be a long way off in the UK (due to the Brexit-induced slowdown), it is expected in the United States.

Donald Trump’s presidency might have rattled markets and delay that somewhat, but it is likely that the future path is upwards. Value stocks can outperform in such an environment.

While this relates to equities, it also rings true for investments in bonds, with expensive sovereigns (the darlings of the past 35 years) under the most pressure.

Within fixed income, we advocate allocating to smaller companies that are less susceptible to the forces of rising interest rates (and the negative effect this has on bonds).

Furthermore, smaller corporations in Europe – one of our preferred regions – are much less exposed to passive buying and the distortions this sort of ownership can create in times of stress.

Smaller European corporates and asset backed securities offer a healthy yield (approximately 6 per cent), which provides an attractive return and a healthy cushion should markets sell off.

I would finish by drawing a distinction between assets that are priced to perfection and those that have a margin of safety built into what can be viewed as historically cheap valuations.

Solely investing in traditional assets is a game that is long in the tooth and has grave risks of not providing protection or diversification from unforeseen events.

We advocate protection through both cheaper valuations but also portfolio construction that involves dynamic asset allocation and owning a much broader swathe of assets than has traditionally been the norm.

Rory McPherson is head of investment strategy at Psigma